When the Future Is Mortgaged: Democracy, Austerity, and the Crisis of Political Imagination

By Ikram Ben Said

This week, as the world’s financial elite gathers in Washington for the IMF–World Bank Annual Meetings, ministers and technocrats will once again debate how to stabilize markets, reduce fiscal deficits, and restore confidence. But outside those halls, people are losing confidence in something far more fundamental: governance itself, and the promise of democracy.

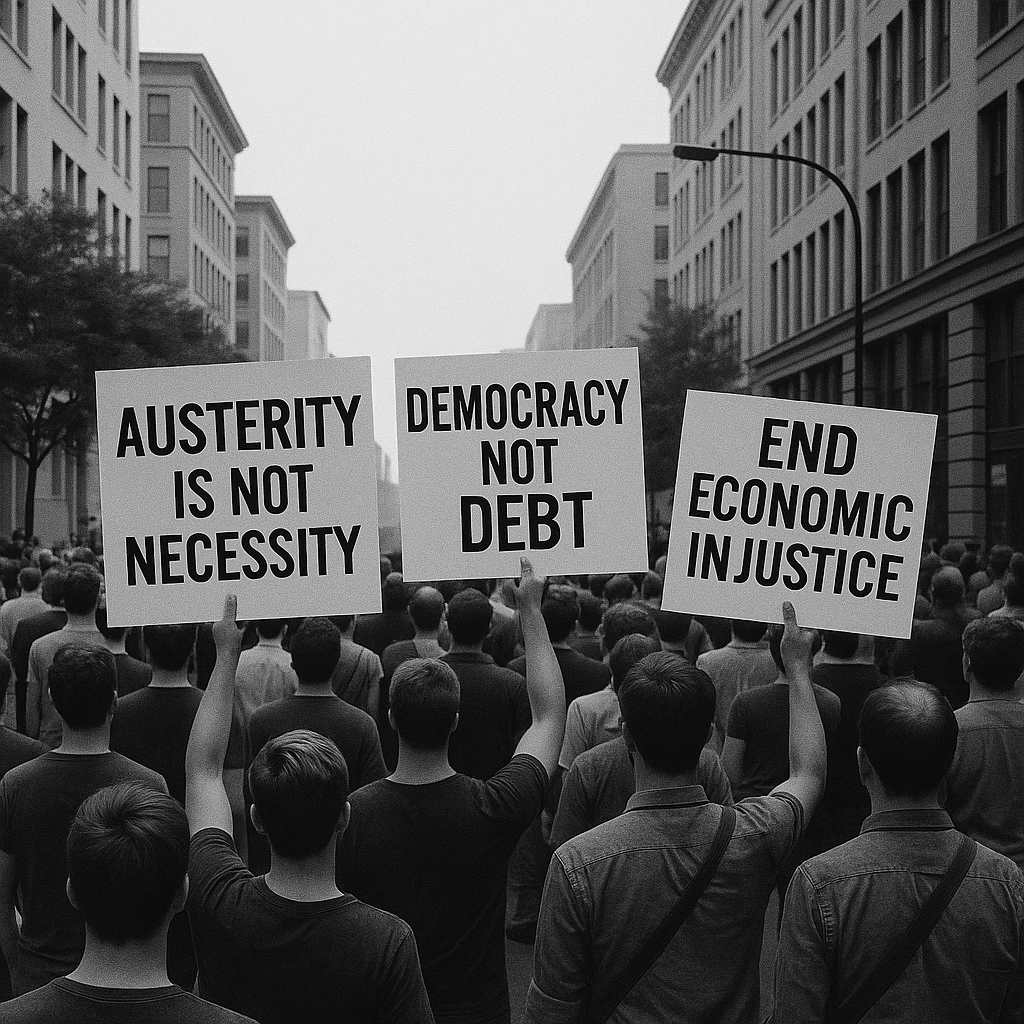

From Rabat to Nairobi, from Kathmandu to Gabès, people are rising against social and economic injustices. Across countries, citizens are discovering that real power no longer lies with those they elect, but with those who lend. Governments are bound by loan conditions that dictate what can be spent, what must be cut, and who gets to decide. Budgets are negotiated between finance ministers and creditors, while parliaments simply approve them, often without debating what they mean for the constituencies that were never consulted.

This is not an abstract issue. Oxfam’s analysis reveals that 94 percent of countries holding World Bank or IMF loans have reduced investments in education, health, and social protection over the past two years [1], a pattern that underscores how austerity has become a near-universal condition attached to global lending.

According to IMF data, the average low-income country now spends approximately 14 percent of its revenue on foreign debt service, up from 6 percent a decade ago, and reaching 25 percent in some cases. [2] When domestic debt is included, the burden rises to an average of 38 percent of revenues, and exceeds 50 percent in parts of Africa. [3]

These are not just fiscal choices. They are democratic ones.

A democratic deficit

In theory, loans are meant to help governments reform and grow. In practice, they often erode the very sovereignty needed to govern. Policies are negotiated behind closed doors, far from public scrutiny. The consequences are everywhere: rising unemployment, shrinking public services, and citizens so disillusioned that voting feels less like a right and more like a ritual.

Governments defend these decisions as “unavoidable.” But what’s really being avoided is political accountability. Leaders seek legitimacy not from their citizens but from their creditors. Debt becomes both a financial and political dependency, one that rewards compliance over courage, and silence over sovereignty.

In authoritarian regimes, where civic space is rapidly shrinking, even discussing public debt can be life-threatening. Activists who attempt to explain what these loans mean for ordinary people or demand transparency and accountability risk harassment, arrest, or worse. The very people fighting to make democracy meaningful are silenced for asking who borrows, who benefits, and who pays the price. The consequences are measurable.

When citizens stop believing that democracy can deliver economic justice, they stop defending it. People are not rejecting democracy. They are rejecting choiceless democracy, a system where elections change faces, not policies. They want a democracy that delivers dignity, not austerity. Therefore, the street’s response takes the form of social unrest, instability, and uprisings often met with state violence through police repression and military deployment. And yet, this erosion of faith is not only the fault of international institutions only. Governments themselves are complicit. They choose opacity over participation, obedience over imagination. They invoke “technical necessity” to disguise political convenience.

International financial institutions often claim to be “apolitical,” mere technocratic bodies concerned with numbers, not power. Yet history tells another story. The IMF and World Bank have rarely hesitated to work hand in hand with dictatorships, approving billion-dollar programs while citizens face repression. Loans have always flowed freely in the name of “stability,” even as human rights were crushed. Meanwhile, countries that experiment with alternative or left-leaning economic models often find themselves isolated or disciplined under the banner of “restoring confidence.” These are not neutral choices; they are profoundly political ones that sustain unequal regimes and silence democratic accountability.

Let’s be honest: we can hardly expect the IMF and World Bank to preach what they do not practice. These institutions are themselves profoundly undemocratic. At the International Monetary Fund, power is literally priced. Voting shares are tied to each country’s financial contribution, meaning money translates directly into influence. The United States, for instance, holds 17.4 percent of the IMF’s quotas, giving it 16.5 percent of the votes. That’s enough for a de facto veto: any major decision, from admitting new member-states to changing the Fund’s mandate, requires an 85 percent majority [4]. By contrast, the entire African continent, which represents the largest group of member states, holds only 6.6 percent of the IMF’s total voting power [5]. The World Bank follows the same logic, where wealth determines influence, not population or need. Even leadership reflects this imbalance: the IMF’s managing director has always been European, and the World Bank’s president has always been American, a colonial-era tradition dressed up as global governance.

The Crisis of Political Imagination

The current global order has not only constrained economies, but it has also colonized the imagination. For decades, the IMF, World Bank, and their allies have defined the limits of what is “possible,” narrowing political debate to the arithmetic of debt and deficit. Governments are told that sovereignty ends where fiscal ceilings begin; that democracy must fit within the margins of creditor confidence. Citizens no longer experience democracy as a space of choice, but as a cycle of compliance and obedience to economic orthodoxy disguised as technical necessity.

When economic decisions are dictated externally, it is not only fiscal sovereignty that disappears, but also the political imagination needed to design alternatives. Ask aloud: What would a world without the IMF or the World Bank look like? And you’ll be met with raised eyebrows, warnings of chaos, or accusations of anarchism. Dare to ask how far credit rating agencies can be politically weaponized, and you’ll see the same unease: people rushing to defend the supposed neutrality of markets. These reactions reveal the depth of our conditioning; even those most harmed by the system have been taught to fear imagining beyond it.

This has created a profound crisis of political imagination: a world in which leaders fear to imagine beyond austerity, activists are forced to defend the minimum from within the same system they challenge, and societies forget that alternatives ever existed. Reclaiming democracy, then, begins not with another round of institutional reform, but with freeing our collective imagination from the tyranny of inevitability, daring to envision economies organized around care, equity, and self-determination.

Conclusion

If the IMF and World Bank want to claim a role in shaping the future, they must first confront their past and the power imbalances embedded in their very design. Reform means little if citizens remain excluded from the decisions that define their lives. That begins with recognizing that debt is not only an economic issue, it is a democratic one. It defines who decides, who benefits, and who bears the cost. The alternative is not chaos; it is courage. The courage to reimagine a world where economic cooperation is grounded not in fear or dependency, but in fairness, transparency, and shared sovereignty. The courage to reimagine a world where rating agencies do not determine people’s destinies, and where international financial institutions no longer press their knees on the necks of entire nations. Because, if you haven’t noticed yet, the world is suffocating.

Ikram Ben Said

Feminist

Co-Founder of New Visions

[2] How to Ease Rising External Debt-Service Pressures in Low-Income Countries

[3] Debt_Service_Watch_Briefing_Final_Word_EN_0910.pdf

[5] Africa leaders see extra IMF seat as starting block for bigger voice | Reuters